In September of 2018, I became a dad for the first time.

What followed were seven months of torture. Beautiful, unfathomable torture. Obviously, this was interspersed with the happiest times in my life, getting to know my new son and learning the ins-and-outs of fatherhood. The torture I refer to largely revolved around one blindingly obvious fact. Babies are rubbish at sleeping.

Sleep-deprivation does funny things to a person. Anxiety, stress and irritability are quickly ramped up to max. I had what can only be described as insane waking nightmares. A mixture of disorientation and clumsiness almost saw me off after one particularly difficult night, and I very nearly fell down a full flight of stairs. But the worst of it? I've never had such terrible arguments with my wife. In hindsight, the subject of the full-blown-barneys were laughable. I think at one point we argued over arrangement of cereal boxes in the cupboard.

For the parents out there, you will understand why the subject of babies and sleep-deprivation are so eternally bound, and how (in an admittedly rather roundabout fashion) my experience of survival on sleep measured in minutes, instead of hours, provides a neat segue into the actual subject of this article.

Simple solutions

In 2018 the staff at Buckley Hall Prison did something extraordinary. In a prison where 70% of inmates are considered high-risk offenders, incidents of violent crime were cut by 50% almost overnight. How did they achieve this? The prison administration provided 50p foam ear plugs to all inmates - that's it. The result of prisoners getting a good night's sleep saw an unprecedented reduction in violent behaviour - a stark but powerful reminder of the importance of sleep to our mental, and as a result, physical welfare.

It' not just the inmates, either. Work in Mind, a knowledge platform dedicated to the connection between buildings and wellbeing, recently published an article highlighting the terrible strain put on prison officers as a result of experiencing violence and aggression at work. The study behind the article showed that many prison officers had trouble switching off, and as a result "these officers were more likely to suffer from sleeping problems, including insomnia and nightmares”. The knock-on effect is a threat to the physical safety of both officers and inmates - and don't think this is a uniquely British problem. Shockingly, the average life expectancy of a prison officer in the US is just 59 years of age. Let that sink in. The results of stress, hypertension, alcoholism and suicide as a result of the nature of the job means the average US prison officer will not live to see their 60th birthday.

The worldwide debate on prison reforms and rehabilitation is not a new one. For many years the Scandinavian prison system has driven world-leading results in the successful rehabilitation and reintroduction of prisoners. 'How?' is a hugely complicated answer that would require a complete systemic overhaul in the UK. In short, it's cultural differences in approach. Giving prisoners 'real rights', and as in Denmark, acting on the philosophy that "there is no punishment so effective as punishment that nowhere announces the intention to punish", and in Norway: “The punishment is the restriction of liberty; no other rights have been removed”.

Given the political and divisive nature of the rehabilitation vs. punishment debate, I wouldn't be so bold as to suggest we should overhaul our entire justice system to align with the Scandinavian model. But there must be more we can do to improve not only rehabilitation but also the physical safety and mental health of those inside our prisons? Perhaps, if not systemic or behavioural, there is an engineering solution?

"And finally!" I hear you cry, he's managed to dance around the crux of it for 600-odd words, but here we are. Yes, I'm an engineer, but here's one thing we can surely all agree on: reducing rates of violent crime in prisons has to be a good thing. Assaults on prison staff are at an all-time high in the UK and a potential solution lies within our technical hands.

So, just like our friends at Buckley Hall Prison, perhaps the introduction of cheap earplugs across the board is a step in the right direction. But if this easy fix can provide a reduction in violent crime by up to 50%, imagine the results of designing a prison from the ground-up with health and wellbeing in mind. Would it be even more effective in reducing violence? Would it provide a significant improvement in rehabilitation? Would it help protect our prison officers? There's only one way to find out, and I'm proposing that we have an open discussion about how we design our "correctional facilities" and our motivations for doing so.

Well worth it

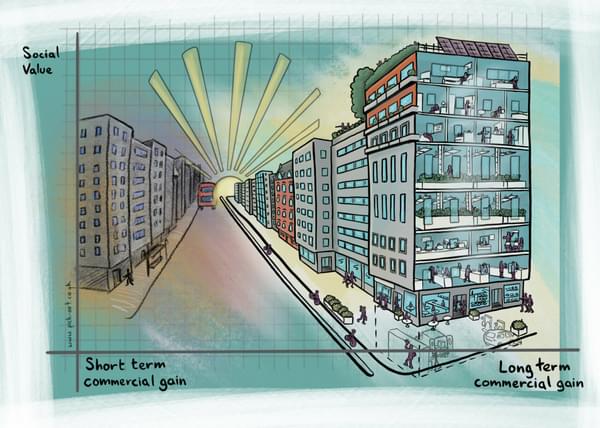

The built environment industry already has thousands of ways of measuring the performance of a building relative to its impact on human health and wellbeing. We know, for example, that access to good daylight and a view of green space improves call handling rates in call centres, and improves retention and exam performance in schools. We also know that through good ventilation design and the monitoring of indoor air quality, we can provide environments in workplaces that are ideal for concentration and minimising errors. Giving people the ability to control their own environment, from temperature to light, has been proven to have a positive emotional impact.

And so, to bring this right back into my wheelhouse, when people are bombarded with unwanted noise; when it affects them during working hours and disturbs sleep; the body's natural response is to produce an abundance of cortisol (the "stress hormone"), resulting in increased blood pressure, heart-rate, anxiety and irritability. This exposure, over long periods of everyday life can lead to heart disease, hypertension and strokes. In the amplified confines of a prison environment, the more immediate threat is angry, irritated occupants with shortened fuses. The result? Spiralling violence in our prisons, affecting both inmates and officers. The short answer to controlling excessive noise is improving sound insulation between cells, improving reverberation time control in common areas to keep chaotic noise to a minimum, controlling noise from building services and ultimately providing a good night's sleep.

If we understand how to optimise building design for wellbeing, and can demonstrate the effectiveness through an abundance of peer-reviewed studies, then perhaps we should be pioneering wellbeing-focussed design standards for prisons, for the good of all society. Who knows how far-reaching the positive effects could be…

I'd like to speak to anyone from psychologists, engineers, prison workers, to contractors with a custodial focus, about what this might look like and how we can push things forward.

This article was originally published by Ric Hampton on LinkedIn.