Have you ever thought of comparing the façade of a building to the intricate leaves on a tree, thinking of it not as a static entity, but as a complicated living being?

Since the pandemic began a lot of buildings have been left barely occupied, if not completely vacant, whilst residential areas and associated buildings, are suddenly bursting with life. Buildings are being occupied and utilised in ways that were not anticipated during the design process and because of this, many buildings are struggling to meet comfort requirements, or be modified to minimise their operational energy.

Optimised buildings: Thinking more creatively about the use of space

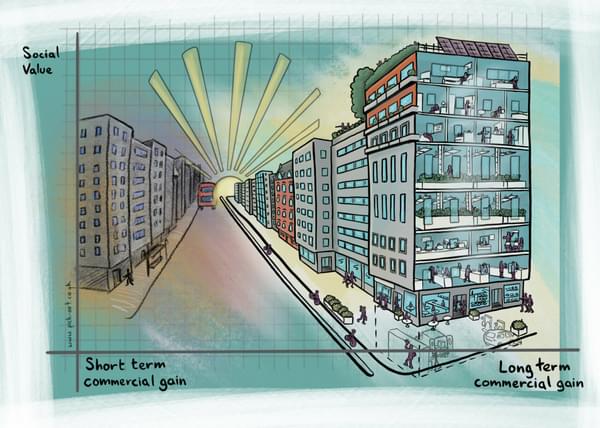

We can be so rigid in our thinking around buildings, especially office buildings. They tower over us, solid concrete and brick monoliths, it is hard to imagine them as flexible living structures. But, now a year into the pandemic, it does beg the question of why we didn't actively use them for something else?

Whilst respecting the need for cleaning and security and the heightened levels of lockdown, could we have used those vast open floor plates as temporary classrooms, giving students space to social distance? Could families cooped up in small gardenless flats have booked a timeslot and used the space for the children to run around, play games, and have a change of scene? Young people stuck in multi-bed house shares, perching on their beds, day after day in a cupboard sized room, could have booked a space in an empty local café, restaurant or office and worked for the day with a desk and WiFi.

“If these ideas might have had their flaws, thinking more creatively about the use of space at least challenges all of us to see our buildings as living beings and not static, one trick ponies.”

Post occupancy evaluation: A shifting working culture requires flexible responses

It often takes a crisis to fundamentally change the way things are done. The oil crisis in the 1970s was the stimulus for Copenhagen to change its entire attitude towards a reliance on fossil fuels and led it on the path to become a carbon neutral city. The public health crises in the Victorian era changed the architecture of hospitals and helped create many of the large green parks we enjoy in our cities. Still in the grip of the pandemic it’s hard to understand what the lessons learned will be, however what we have seen are the empty streets in the centre of London and other major cities, our glass towers deserted, and working life viewed on the screens from our home offices. There has already been a shift in our working culture and whether we all return to the office or not, we have seen our buildings are not flexible enough, they are not controlled enough and they leak energy unnecessarily.

Energy Efficiency: Tackling the performance gap

In an age when carbon emissions are under the microscope, our buildings should be built to last. They should be fit for the occupants who use them and adaptable to change. As architects, engineers, developers and contractors, once we hand over our design and the building’s constructed, that cannot be the end of our involvement with it. Like any complicated machine, or living being, things go wrong, things need to be checked and corrected and adjusted. We need to take responsibility for our buildings working as efficiently as possible and using as little energy as possible. When a building or a floor is empty, we need to be able to stop the use of energy and then act creatively and flexibly to find other uses for the space. Buildings need to be designed, constructed and operated to be able to adapt to these changes.

Often it doesn't take a lot to fine tune a building to make small corrections to get it back on track. But the impact of those small changes on carbon emissions, operational cost and user experience can be disproportionately higher.

Framed in the context of increasing urgency around reaching global net zero targets, there should be regular reviews of how buildings are supposed to work and how they are being used to make sure we are optimising building performance and reducing energy usage wherever possible, rather than furiously expending energy because a small control detail has gone awry.

We shouldn't leave them after that short period of design and build and expect them to live for thirty, fifty, a hundred years in a static state. We need to check their health and wellbeing once in a while and see buildings differently, as a living being that needs to be looked after.