Back to Articles

Are electric vehicles changing the way we hear our cities?

Eddy Goldsmith \ 20th Sept 2019

Electric vehicles have surged in popularity in the last 10 years, and are expected to fully replace conventional vehicles by as soon as 2030. With zero exhaust emissions and renewable energy options, it’s easy to see the appeal. But what will their widespread adoption mean for the human experience of the urban environment?

As they are almost silent at lower speeds, electric vehicles are potentially dangerous to humans, as we cannot always hear them coming. Research suggests that pedestrians are at a 40% greater risk of being in a collision with an electric or hybrid car than standard petrol or diesel. However, from July 1 2019, all new electric cars sold in the EU have to be fitted with an Acoustic Vehicle Alerting System (AVAS) –an artificial noise – to create a safer environment within our cities.

The new EU Regulations state that electric vehicles travelling at speeds less than 20kmh must emit a sound that is indicative of vehicle behaviour, meaning the character of sound will change to correspond with acceleration, and be between 56dB and 75dB (at 2m).

The Jaguar I-Pace AVAS system sounds a lot like the Millennium Falcon, whereas the sound of the Nissan Leaf system is more analogous with a faulty washing machine. Even though the EU requires a continuous and progressive sound there is certainly an element of artistry and branding within the design of the AVAS systems for each manufacturer, so we could expect lots of strange-sounding electric vehicles whizzing around our cities.

Evolving Urban Soundscapes

An interesting question within all this is how our inner-city soundscapes might be affected. Although the overall shift towards electric vehicles is likely to reduce noise levels from road traffic, will it really contribute quality of life and wellbeing? These safety systems are designed to grab the attention of pedestrians, for their own safety, and are therefore likely to be inadvertently disruptive to people who aren’t at risk.

Are we at risk of creating a disorientating sci-fi soundscape within our cities, as an unwanted side effect to improving air quality and road safety?

This could change the dynamic between background and foreground sounds within urban areas, making all sorts of urban sounds you may not have noticed before more clearly perceptible. Vibrant city centres could actually become increasingly disruptive to the people living and working there.

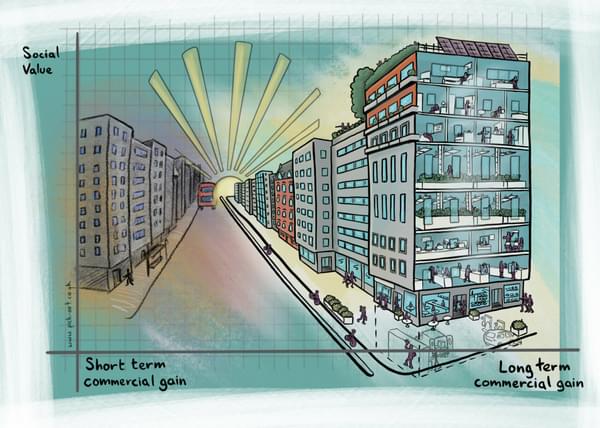

The National Planning Policy Framework tells us to support “strong, vibrant and healthy communities” and the Noise Policy Statement for England tells us to “contribute to improvement of health and quality of life”. The majority of noise guidance, however, measures overall noise levels in decibels, and does not fully consider environmental and social context that is harder to quantify. The level of noise alone is not an indicator of wellbeing, or even proportional to quality of life. Natural sounds such as running water, bird song at a relatively high level of decibels could still be enjoyable.

Soundscape interventions

The opportunity to purposefully introduce sounds into an acoustic environment with the intention of improving the quality of life in the local community is rare. However, soundscape interventions can present effective solutions to unconventional acoustic problems. By incorporating comprehensive acoustic principles in urban planning, such as masking, attention grabbing and listener states, rather than the traditional approach of mitigate and reduce, we can foster a better environment for future generations, that meets the objectives of UK Planning Policy in the long term.

How are these principles implemented? The addition of natural or pleasant sound sources to urban soundscapes, places of work or our homes can divert people’s attention from disruptive sounds, the perception of which is intertwined with the visual experience of the listener. For example, when distant road traffic noise is superimposed over a video of a waterfall, the sound is likely to be perceived as the pleasing sound of running water.

More stimulating and artistic sounds have been successfully incorporated in to urban design with success in creating vibrant spaces. One example is the Sea Organ of Zadar, Croatia: a 70m long instrument that harnesses the natural flow of the Adriatic Sea to create a constant hypnotic melody. Ultimately, this area now provides functional urban open space, serving as a place for relaxation, contemplation and conversation for the local community.

Offering value

By thinking in advance about how the implementation of new technology could change acoustic landscapes, we should adapt, and develop the way in which we approach acoustic design in the context of urban planning.

In a land of ever-evolving cities, an innovative design philosophy is essential in creating well balanced, exciting urban environments which maximise value to local residents and wider communities.

If you need help with urban soundscapes, preserving natural ones or have a project with a focus on acoustic wellbeing, please get in touch at acoustics@hydrock.com.

This article was originally published by Eddy Goldsmith on LinkedIn.