Just like a jigsaw puzzle, a transport strategy is made up of many different pieces that need to be fitted together in the right way in order to create a successful system that suits the needs of its users.

The Transport Select Committee is currently running an inquiry into how the government sets its strategic transport objectives.

The Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) submitted written evidence to the committee, which drew on a consultation that they ran over the summer and its policy position statement on a national transport strategy for England. As Trustee for Policy and External Affairs for ICE, I was recently invited to give evidence to the Committee inquiry at Westminster — a privilege I don’t take for granted and so I was keen to represent the voice of an industry that deserves clarity from the top.

Why do we need a transport strategy?

Transport has a key role in improving people’s lives and meeting the UK’s long-term objectives — net zero, climate risk and resilience, reducing social and economic inequalities between regions and achieving the 2030 UN Sustainable Development Goals.

But all too often transport investment fails to align with those goals. In many parts of the country poor connectivity is limiting people’s opportunities — for example, Bradford is one of the youngest and fastest growing cities in Europe, yet its rail connections to Leeds and Manchester are beyond slow and unreliable. I’m currently working on a project to bring a new mainline station to Rotherham, which is a town that’s only been served by an hourly branch line service since the 1980s.

Furthermore, uncertainty about the government’s long-term objectives for transport is causing stop-start delivery of major projects, as we’ve seen with the hugely frustrating decisions about the northern phase of HS2.

In turn, this drives up the cost of infrastructure and drags out (by decades!) when people and businesses will enjoy the benefits of well-orchestrated transport investment.

Strategic transport objectives: An industry waiting on the platform

At the Transport Select Committee, the key lines of enquiry were founded in how the government articulates its strategic transport objectives, and whether they are the right ones?

I’m honest enough to say that when responding to that question, my first thought was to try to remember where these strategic transport objectives are actually set out? Are they in the (now defunct) Integrated Rail Plan? The recent Plan for Drivers? The Cycling and Walking Strategy? Bus Back Better? The Transport Decarbonisation Plan?

And these are just the transport policy documents — if we’re thinking about some of the biggest challenges facing society at the moment, what about the Levelling Up White Paper? The Net Zero Strategy? The old Industrial Strategy anyone?!

Our policies, transport or otherwise, are a tangled mess, a bureaucratic nightmare that are difficult to understand and offer no clear direction to those charged with improving the system. As a result, decarbonisation and climate adaptation are rapidly falling off-track.

From puzzle pieces to a unified system

What we have is a whole load of different policies and strategies, driven by separate objectives of different Whitehall departments, but a lack of clarity over what the core objectives that any transport system should seek to achieve.

It’s like a jigsaw. Many of the documents that I’ve listed are corner or edge pieces, that help to define the overall shape and give some structure to what the end product is meant to be. Beyond that, the series of interventions, schemes and initiatives remain a pile of pieces, of different shape and size, which need to be sorted and shuffled around as we try to find the right fit.

We’re missing the picture on the front of the box — a clear definition of the outcomes that we’re trying to achieve — including those cross-government outcomes that address the big challenges around decarbonisation and economic inequality.

How to put the pieces together

There are some great examples of how it can be different. For example, Wales has linked its transport strategy to its seven national wellbeing goals in the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. This approach ensures that planning considers a wider range of transport users, journey types and outcomes — including the needs of future generations. The Welsh Government used this approach when reviewing its previous list of roads schemes, resulting in a much more rounded future investment programme that’s linked to clear objectives and which should (hopefully) sit above political changes.

A number of the sub-national transport bodies, notably Transport for the North in its first Strategic Transport Plan, clearly set out the economic, social and environmental objectives it wished to see delivered across the North up to 2050 before going on to review how transport could support those objectives. In cancelling Phase 2 of HS2 and replacing the investment across a number of different projects, it’s interesting to note just how many of those identified by Transport for the North were mentioned in the Network North policy paper — it’s almost as if they were good ideas all along!

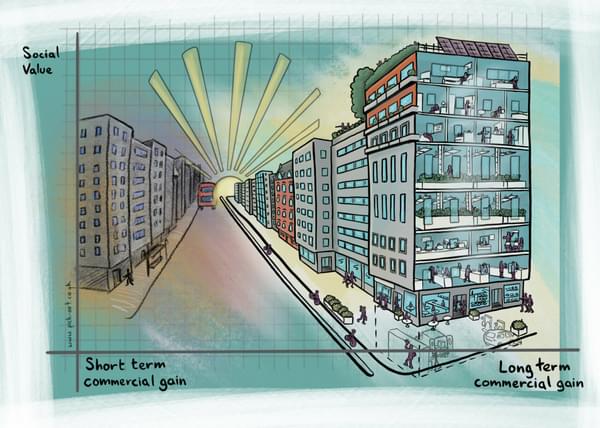

Setting out the picture on the front of the box gives strategic clarity and long-term certainty. A national transport strategy that does this would align the efforts of engineers, policymakers, and other stakeholders towards sustainable road and rail development. It would end the cycle of transport investment decisions that are blinkered, funded in the short term, and disconnected from wider outcomes.

It would allow us to view infrastructure as an investment, not a cost. That doesn’t mean frivolously spending more, but spending wisely by making the right strategic decisions. And committing to delivering them.

As the festive season approaches, many of us will be gathering with family and friends, and maybe, just maybe, a jigsaw will be pulled out from under the couch. Now imagine having to try to complete that jigsaw without the picture on the front of the box, there'd be chaos — that’s how the industry is operating under the guidance of existing transport policy.

The way forward: Clarity and certainty

My concluding remarks to the Committee echoed something Lord Peter Hendy has often said from his experience in London with several mayors of different political persuasion.

If you start with a very clear idea of “why” you may be trying to do something, the transport and engineering profession can then use its combined skills to come up with the “what?” and “how?” to achieve the vision. In turn, leaving the “when?” and the “who?” for decision-makers to confirm and communicate to the public.

The London Mayor is required to develop a London Plan — a spatial and economic framework for a 30-year period to guide development in London. Lord Hendy makes the point that this is a very clear and certain “why?” and each successive Mayor’s Transport Strategy has consequently been very similar as they’re all essentially trying to achieve the same objectives.

If we could replicate that approach at both a national level, and also at a more devolved level with elected mayors, we’d have a strong and stable steer as to what our transport system needs to be.

Cities and regions can develop transport strategies that are effective, efficient, and equitable. And, in turn, our industry can then invest in the skills and resources to deliver this system, confident in the knowledge that politics and opportunism won’t undermine that investment.

Jonathan Spruce is a director of Hydrock Fore, a team of experts providing specialist transport and infrastructure consultancy.