Following the Clean Air Zone consultation this summer, it was announced this week that Bristol City Council has opted to ban diesel cars in the city centre between 7am and 3pm, pending Cabinet approval on Tuesday 5th November 2019.

The requirements for Clean Air Zones are a result of legal action which mandated the UK government to reduce illegal nitrogen dioxide (NO2) pollution as fast as possible.

As a result of this, Defra released the “UK plan for tackling roadside nitrogen dioxide concentrations”. In it, they emphasise the solution to tackling illegal levels of NO2 is to focus on introducing “cleaner” vehicles, and delegated responsibility to Local Authorities.

This is not as simple as it sounds. As the Volkswagen “dieselgate” scandal demonstrated, the science behind exhaust emissions is complex: The best new diesels actually emit less nitrogen oxides (NOx) than the best petrol engines, while the worst don’t even meet euro 1 standards.

Climate emergency

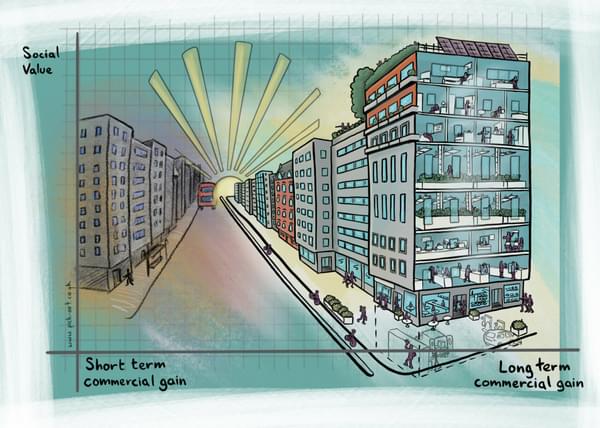

To only focus on vehicle exhaust emissions misses the elephant in the room: energy consumption.

We are driving vehicles that can weigh nearly 20 times the average human and are occupied on average by 1.1 passengers.

These vehicles are then powered by an engine that runs with a 5% - 40% efficiency (5% = sports car in urban area, and 40% diesel vehicle on a motorway). Contrast this with an electric motor, which is around 90% efficient, or a modern gas boiler at home that turns nearly 100% of natural gas into heat, and the level of wasted energy begins to emerge.

To put this into context, a 30-mile car journey in a large petrol car uses the same energy as an average family uses in electricity in a week.

NOx versus CO2

Whilst better catalytic converters on new vehicles has lowered NOx emissions, the trend for CO2 emissions is in the other direction.

Diesels on average emit 18% less CO2 than petrol engines. If Bristol’s diesel ban causes drivers to simply switch to petrol, there will be an overall increase in CO2 emissions, which the evidence shows is far more pressing.

“A 30-mile car journey in a large petrol car uses the same energy as an average family uses in electricity in a week.”

“Fastest route to compliance”

Despite the Bristol public consistently asking for better walking, cycling and public transport, the Local Authorities have stated they are mandated to go with the “fastest route to compliance”. To find what this fastest route is, they have been using a dispersion model.

Dispersion models give an air quality consultant three options to reduce traffic-led emissions:

- increase the (average) speed of traffic;

- reduce the number of cars; and/or

- reduce the emissions factors from these cars (improve the “fleet”).

Number one is difficult to achieve without number two; number two is seen as politically sensitive; and number three is a Clean Air Zone.

Bristol’s Clean Air Zone diesel ban solution expected to reduce roadside NO2 concentrations by only 8%.

UK mayors have lobbied for £1.5bn of funding to tackle Britain’s air pollution issue, with £220 million allocated for Clean Air Zones. However alternatives that show faster routes to compliance and a greater portfolio of benefits include:

Cycle Superhighways: Monitoring sites next to London’s new cycle superhighways have shown NO2 concentrations have fallen by around 20% as soon as work began. Manchester is on course to implement the largest cycle network in the UK, designed to be used by children as young as 12.

20mph: Whilst the only enforced 20mph section in the entire country, Tower Bridge London, has no air quality monitoring data, other methods such as microsimulation modelling shows that if drivers stuck to 20mph, roadside concentrations of NO2 would drop by 60% (because accelerating to 30mph requires 100% more energy than to 20mph, despite it only being 50% faster).

Green Waves: Synchronising traffic signals reduces stops and starts. Drivers who stick to the speed limit will go through one green signal, and then the next, but the success is heavily reliant on driver awareness/education. The approach was found to be a very effective measure for reducing NO2 in a 2017 BBC Documentary, “Fighting for Air”.

Bristol, like central government, has separate policies for climate change, air pollution and road safety, yet the answer to them all lies in addressing how people and goods get from A to B.

Despite the name, Clean Air Zones will have a minimal impact on air quality. Quicker, more effective solutions that would have far wider reaching benefits are available, and in many cases are already being done, but simply need more support.

For more information visit our Air Quality page.

This article was originally published by Blaise Kelly on Linked In.